HOW NEUROSCIENCE EXPLAINS HABITS AND BEHAVIOR CHANGE

- Marcela Emilia Silva do Valle Pereira Ma Emilia

- Jul 29, 2025

- 6 min read

🧠 How Neuroscience Explains Habits and Behavior Change

Why is it so hard to change a habit, even when we know it's harmful?

That’s an old question — and modern neuroscience has a lot to say about it.

Over the past few decades, scientists have discovered that our routine behaviors are not just poorly made decisions or a lack of willpower: they have deep roots in the brain’s automatic functioning. And more than that — understanding how habits work might be the key to changing them.

🧩 1. What are habits from a neuroscience perspective?

Habits are behaviors that become automatic through repetition. They are actions and attitudes that are repeated regularly due to environmental cues, context, or routine. In brain terms, this means that over time, the brain transfers an action from conscious control (slower and more effortful — the kind that requires thinking before doing) to a fast and unconscious route (quicker and energy-efficient — the autopilot mode).

This process mainly involves the basal ganglia, deep brain structures that serve as automation centers for routines. When a behavior is repeated and rewarded, the brain "learns" to conserve energy by assigning this task to the basal ganglia. The conscious decision-making that once relied on the prefrontal cortex is now replaced by automatic execution.

Neuroscience shows us that habits serve an essential adaptive role: by saving mental and physical energy, the brain can redirect those resources to more demanding or relevant tasks.

🔬 Studies show that:

Habits are not innate behaviors

They require slow learning, and once consolidated, they are difficult to change

Attentional mechanisms are necessary for habit formation

📚 Charles Duhigg, in The Power of Habit, proposes the habit structure:

Cue → Routine → Reward

*The basal ganglia are a group of forebrain nuclei including the striatum (caudate nucleus and putamen) and the globus pallidus. The subthalamic nucleus and substantia nigra also form part of the basal ganglia circuit, although they are not physically located within the basal ganglia itself.

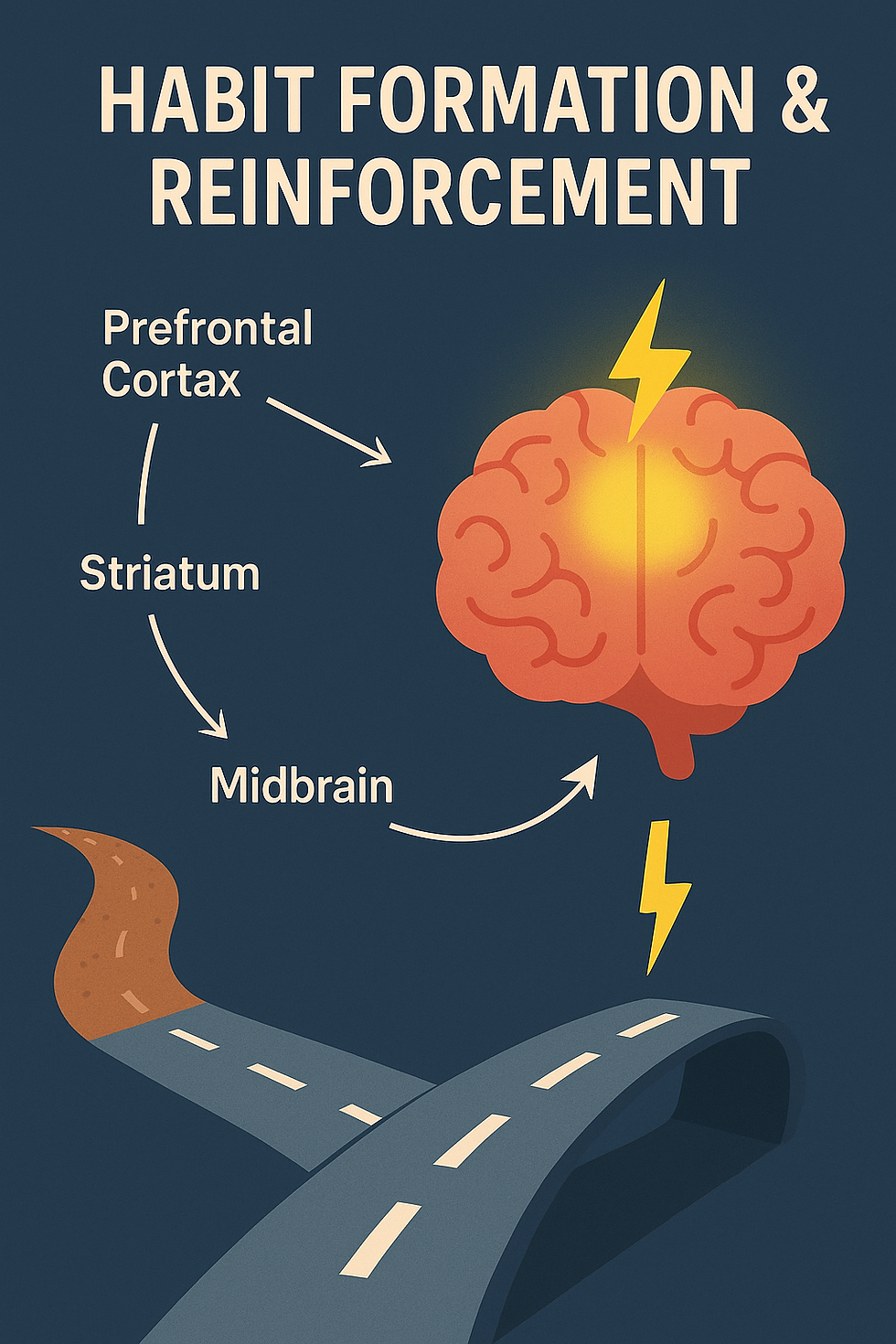

🔁 2. How are habits formed and reinforced in the brain?

Every time we repeat an action that produces a positive feeling — even a small one — dopamine is released. This neurotransmitter is key to the reward system. The more we repeat a behavior, the stronger the neural pathway becomes — like a trail being walked until it becomes a paved road.

It all starts in the prefrontal cortex, which identifies the behavior. This is then passed to the striatum, which learns the pattern and communicates with the midbrain to evaluate how much dopamine was released. When this circuit works well, it creates positive reinforcement, helping the brain determine what works and what doesn’t. If repeated often, a feedback loop forms between the sensorimotor cortex and the striatum, creating a semi-permanent routine — a habit.

🧠 This entire circuit allows the habit to enter autopilot: the motor response and dopamine release are already “pre-programmed.”

This kind of habit is also referred to as procedural memory — an implicit memory containing information we aren’t even aware we possess.

According to neuroscientist Ann Graybiel (MIT), habits consolidate in the brain as “chunks” of automatic action. A classic study by Wolfram Schultz (1997) showed that the dopamine system is activated not only by the reward itself but by the anticipation of it — which helps explain why some behaviors are so hard to resist.

⚙️ Habits are indeed formed through daily activities aimed at achieving a specific goal. The repetition of behavior in a particular context creates implicit memories, linking the environment to the behavior. Over time, the original motivation (intention, goal, or reward) becomes less important, and the system keeps running simply because it's efficient.

🚫 3. Habits and negative stimuli

Neuroscientific studies suggest that we also form habits to avoid negative outcomes.

What does this mean? A behavior can become a habit if it’s frequently used to avoid a negative result — and this type of habit often forms faster than routine-based habits. This may be due to the amygdala hijack, when the amygdala takes control of behavior in response to stress or perceived threat.

Although the exact neural pathway is still unclear, behaviors designed to avoid punishment, disapproval, or social discomfort tend to become automatic faster, possibly due to the exposure to stress during learning.

🔺 Habits formed under aversive conditions may not require reward to persist — they are reinforced through emotional avoidance.

🧠 4. The challenge of change: why is it so hard to break a habit?

Our brain loves predictability. It prefers familiar paths, even when they aren’t ideal. That’s because change requires effort from the rational system (System 2), while habits operate in automatic mode (System 1), as described by Daniel Kahneman.

📌 The difficulty in breaking a habit lies in attentional processes: environmental cues trigger automatic responses. We already know the expected reward — that’s why resisting is so hard. Studies have shown that stimuli previously associated with known rewards tend to capture attention more easily, especially if the reward is pleasurable.

But breaking a habit is not just about stopping the behavior. It requires breaking the loop:

Identify the cue

Replace the routine

Maintain or substitute the reward

💥 This demands more cognitive resources than usual, leading to increased energy consumption — which in turn can deplete mental energy available for other important functions. In the case of deeply ingrained or compulsive behaviors, this process may cause adverse effects similar to withdrawal symptoms.

That’s why diets fail, New Year’s resolutions vanish, and quitting addictions feels overwhelming: you're trying to reprogram a system built for efficiency.

But not every habit change has to be difficult. 😉

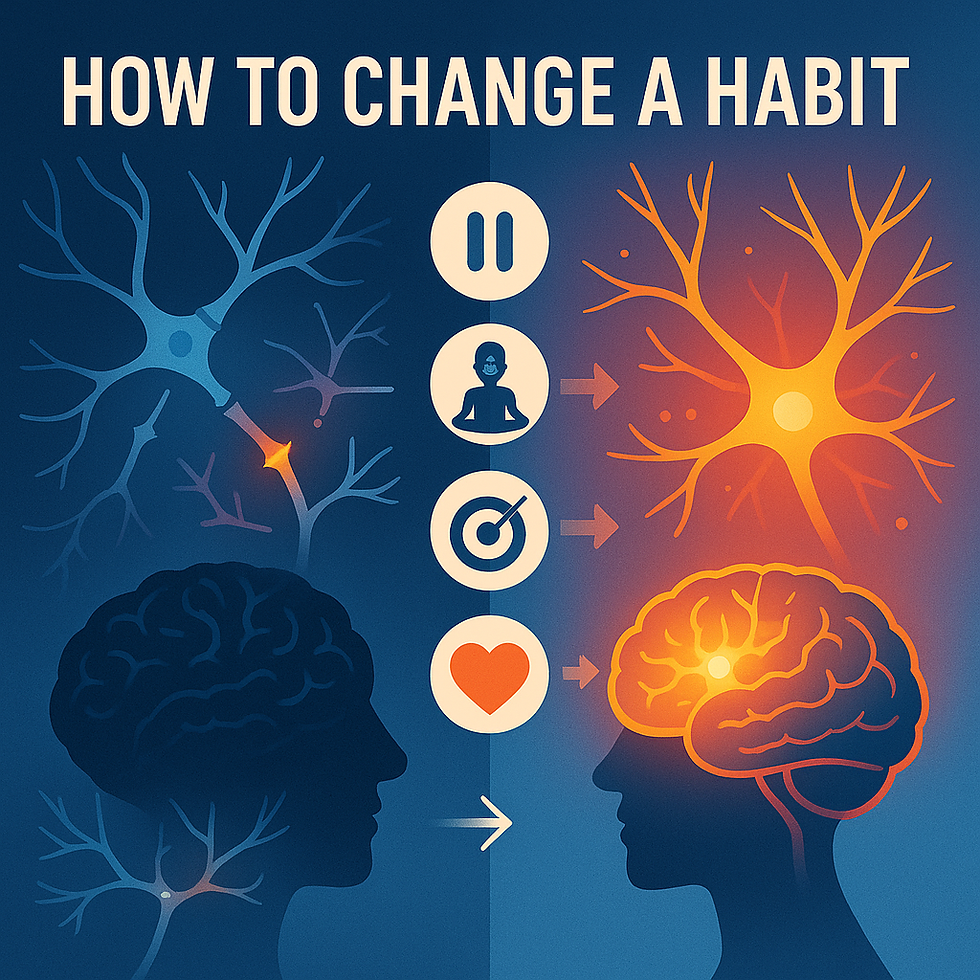

🔄 5. How does neuroscience explain behavior change?

🧠 The good news: the brain can learn to change.

💡 Environmental change is a strong catalyst: new contexts, people, and experiences help interrupt the habit loop. Technological evolution is a great example — we’ve gone from vinyl records to music streaming in the cloud, and from landline phones to real-time video calls.

The key to change lies in neuroplasticity — the brain’s ability to create new neural pathways using neurons that were underutilized.

Even more importantly, habits are stored in the brain as procedural memories, separate from where we create goals and intentions. So when a new reward or motivation emerges, change becomes more attainable.

🔧 Practices that support habit change include:

🧘 Mindfulness: activates the prefrontal cortex and shifts behavior out of autopilot

⏸️ Deliberate pauses: interrupting behavior at the cue stage creates space for new learning

🔁 Conscious repetition: strengthens the new neural circuits

❤️ Emotion-based reinforcement: if the new habit is emotionally meaningful or enjoyable, it has a higher chance of sticking

🧠 Replacing a habit is more effective than trying to erase it. And small, repeated changes tend to work better than grand, unsustainable attempts.

🛠️ 6. Practical applications

Neuroscience-based knowledge about habits is already being applied in several fields:

🧠 Psychology and behavioral therapy

🚭 Addiction recovery and rehabilitation programs

🥗 Lifestyle changes (sleep, diet, exercise)

🎓 Education and workplace training

🧩 Environmental and behavioral design for better decision-making

Professionals in healthcare, education, leadership, and public policy benefit greatly from understanding how the brain “prefers” routines — and how to create the right conditions for behavioral change.

✅ Conclusion

Changing habits is not just a matter of willpower — it's a neurobiological journey.And from a neuroscience perspective, it’s a fascinating trip through our primitive brain.

The human brain is plastic, adaptable, and incredible. But it’s also lazy — especially when it comes to changing patterns.

That’s why understanding how the brain operates can be the first step to effectively and sustainably changing behavior.

You are not your habits — but you can be the architect of your future ones.

📚 References

Graybiel, A. M. (2008). Habits, rituals, and the evaluative brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 31, 359–387.

Duhigg, C. (2012). The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business.

Schultz, W. (1997). Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology, 80(1), 1–27.

Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213–225.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Comments